Chapter 7 Some number theory

7.1 Divisors and prime numbers

Let us recall the definition of divisor and prime numbers

Definition 7.1 (divisor) Given two natural numbers \(n\) and \(m\) we say \(n\) is a divisor of \(m\) (or \(n|m\)) if there exists \(k \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(m=n\times k\).

Definition 7.2 (prime number) While we define divisor it is worth defining a prime number. We call \(p \in \mathbb{N}\) a prime number if the only divisors of \(p\) are \(1, p\).

Now we have some new definitions

Definition 7.3 (greatest common divisor) Given two natural numbers \(n\) and \(m\) a number \(q\) that divides both of them is a common divisor and the largest such number is called the greatest common divisor we write \(gcd(n,m)\).

This allows us to write a better definition of coprime

Definition 7.4 (coprime) If \(gcd(n,m)=1\) then \(n\) and \(m\) are coprime.

Definition 7.5 (least common multiple) Given two numbers \(n\) and \(m\) in \(\mathbb{N}\). Then we define the least common multiple of \(lcm(n,m)\) of \(n\) and \(m\) to be the smallest number \(k\) such that \(n|k\) and \(m|k\).

Lemma 7.1 Given \(n, m \in \mathbb{N}\) then \(lcm(n,m) \times gcd(n,m) = nm\).

Proof. Note in this proof we use the fact that if \(a|bc\) and \(gcd(a,b) =1\) then \(a|c\). This is very similar to the fact that if \(p|ab\) then \(p|a\) or \(p|b\).

Let \(d = gcd(n,m)\). Then we know there exists \(k, j \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(n =kd\) and \(m =jd\). Then we must have \(gcd(k,j) =1\) since otherwise there would be a divisor of \(n,m\) which is larger than \(d\).

Then if we write \(l = lcm(n,m)\). We must have \(kd|l\) and \(jd|l\) so there exists \(a, b\) such that \(l=akd=bjd\). Dividing by \(d\) we know that \(l/d = ak = bj\) so since \(k,j\) are coprime we must have \(j|a\) and \(k|b\) so the least such numbers satisfying this are if \(a=j\) and \(b=k\). Therefore \(l=kjd\).

So \(gcd(n,m)\times lcm(n,m) = kjd^2 = (kd)\times (jd) = nm\).

Theorem 7.1 (division with remainder) Suppose that \(a \in \mathbb{Z}, b \in \mathbb{N}-\{0\}\) then there exists \(q \in \mathbb{Z}\) and \(r \in [[b]]\) such that \[ a =bq+r. \]

Proof. If \(b=1\) we just take \(q=a, r=0\) so we can work in the case \(b >1\).

Let us fix \(b\) and prove the result by induction on \(a\). If \(a=1\) then \(a=0\times b+1\). This is the base case.

Now if we assume that there exists \(q,r\) such that \(a-1 = qb +r\) then either \(r \in [[b-1]]\) in which case \(a = qb + (r+1)\) is a solution to our problem, or \(r=b-1\) in which case we write \(a = (q+1)b\).

Example 7.1 How can we find the greatest common divisor of two numbers. One way to do it is by repeated division.

We can apply repeated division with \(81\) and \(51\). We have \[\begin{align*} 81 & = 1 \times 51 + 30,\\ 51 & = 1 \times 30 + 21,\\ 30 & = 1 \times 21 + 9,\\ 21 & = 2 \times 9 + 3,\\ 9 & = 3 \times 3. \end{align*}\]

We can also do this backwards to get \[\begin{align*} 9 & = 3 \times 3,\\ 21 & = 2 \times 9 + 3 = (2 \times 3 +1) \times 3 = 7 \times 3,\\ 30 & = 1 \times 21 + 9 = (1 \times 7 + 3) \times 3 = 10 \times 3,\\ 51 & = (1 \times 10 + 7) \times 3 = 17 \times 3,\\ 81 & = (1 \times 17 + 10) \times 3 = 27 \times 3. \end{align*}\]

And we deduce from the that \(gcd(81,51) = 3\).

Why does this work? We notice that if \(c|a, c|b\) then if \(a=qb+r\) then we must have that \(c|r\). Continuing on if \(c|b\) and \(c|r\) and \(b=q_2 r+ r_2\) then \(c|r_2\) and so on. If eventually you end up with a remainder term which is 0 then we terminate. This shoes that if we terminate with remainder \(r_k\) then \(r_k|a\) and \(r_k| b\) and that nothing larger than \(r_k\) can divide both \(a\) and \(b\).

7.2 Euclid’s Algorithm

Taking inspiration from calculations like the one above we can write down a procedure to find the greatest common divisor of \(a,b\).

Definition 7.6 (Euclid's Algorithm) Given \(a, b \in \mathbb{N}\) with \(a < b\) we can write \[\begin{align*} b &= q_1a + r_1, \quad q_1 \in \mathbb{N}, r_1 \in [[a]],\\ a &= q_2r_1 + r_2, \quad q_2 \in \mathbb{N}, r_2 \in [[r_1]],\\ r_1 &= q_3r_2 + r_3, \quad q_3 \in \mathbb{N}, r_3 \in [[r_2]],\\ r_2 & = \dots \end{align*}\] Eventually this process will terminate because we will have \(r_k = 0\) for some \(k\) and then we have \(r_{k-1} = gcd(a,b)\).

Theorem 7.2 (Euclid's Algorithm) Given the algorithm above we have the following - This algorithm will terminate. i.e. eventually we have \(r_{k-1} = q_{k+1} r_{k} + 0\). - In this case \(r_{k} = gcd(a,b)\) - There exists \(x,y \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(gcd(a,b) = xa+by\).

Proof. We take each point in turn.

Firstly we can see that, for every \(j\), \(r_j> r_{j+1} > r_{j+2}\) so eventually we must get to 0. Therefore the sequence terminates.

Secondly, we prove this by showing that in each step of the algorithm we preserve the set of common divisors. If \(m|r_j\) and \(m|r_{j+1}\) then since \(r_j = q_{j+2}r_{j+1} + r_{j+2}\) so \(m|r_{j+2}\) as well. Equally if \(n|r_{j+1}\) and \(n|r_{j+2}\) then we must have \(n|r_j\) as well. So the set of divisors of \(r_j, r_{j+1}\) is the same as the set of divisors of \(r_{j+1},r_{j+2}\). From this it follows that \(gcd(r_j,r_{j+1})=gcd(r_{j+1},r_{j+2})\). Therefore itterating backwards we have that for every \(j\) that \(gcd(r_j, r_{j+1}) = gcd(a,b)\). Consequently at the point where the algorithm terminates, \(r_k = gcd(r_k,0)=gcd(r_k,r_{k+1})=gcd(a,b)\).

For the last point let us make the claim: For every \(j\) we can write \(r_j = x_j a + y_j b\) for some \(x_j, y_j \in \mathbb{Z}\). Then we can prove this recursively. First we know that \(b=q_1 a + r_1\) so \(r_1 = -q_1 a + 1*b\). Now suppose that \(r_{j-1}, r_{j-2}\) can be expressed as above. We know \(r_{j-2} = q_j r_{j-1} + r_j\) so \(r_j = r_{j-2} - q_j r_{j-1} = x_{j-2} a + y_{j-2} b - q_j(x_{j-1}a + y_{j-1}b) = (x_{j-2}-q_j x_{j-1})a + (y_{j-2} - q_j y_{j-1})b\). So this shows the claim by induction. Now the claim implied in particular that \(r_k = x_k a + y_k b\) proving the third point in the theorem.

7.2.1 Geometric interpretation of Euclid’s algorithm

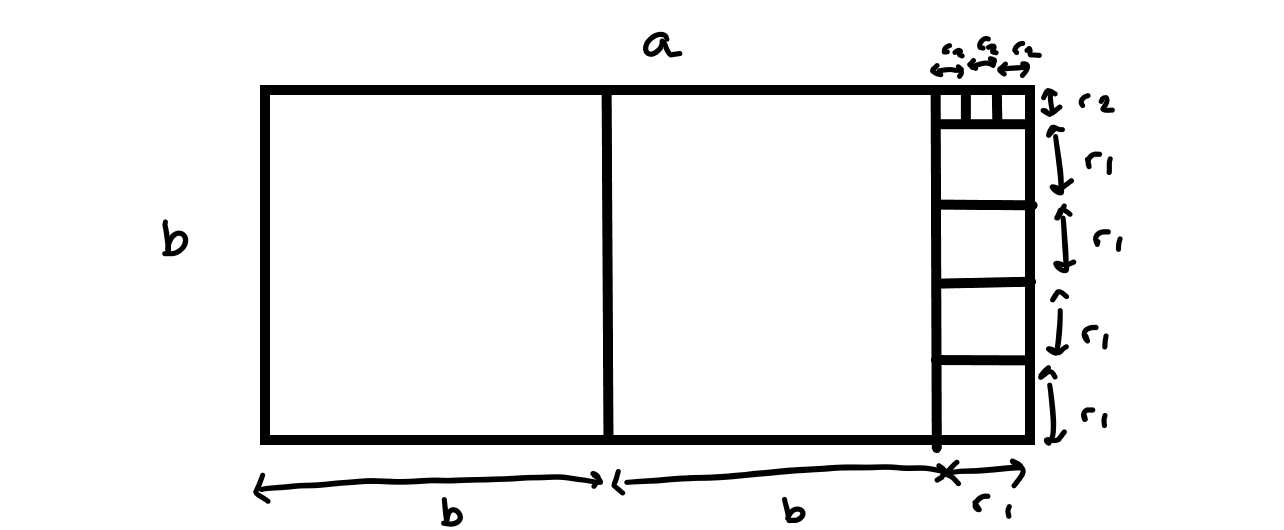

We can think of this algorithm pictorially by drawing a rectangle of length \(a\) and height \(b\) and then \(q_1\) squares of side length \(b\) inside it leaving a rectangle of length \(r_1\) and height \(b\) and so on…

Figure 7.1: Picture showing Euclid’s algorithm pictorially

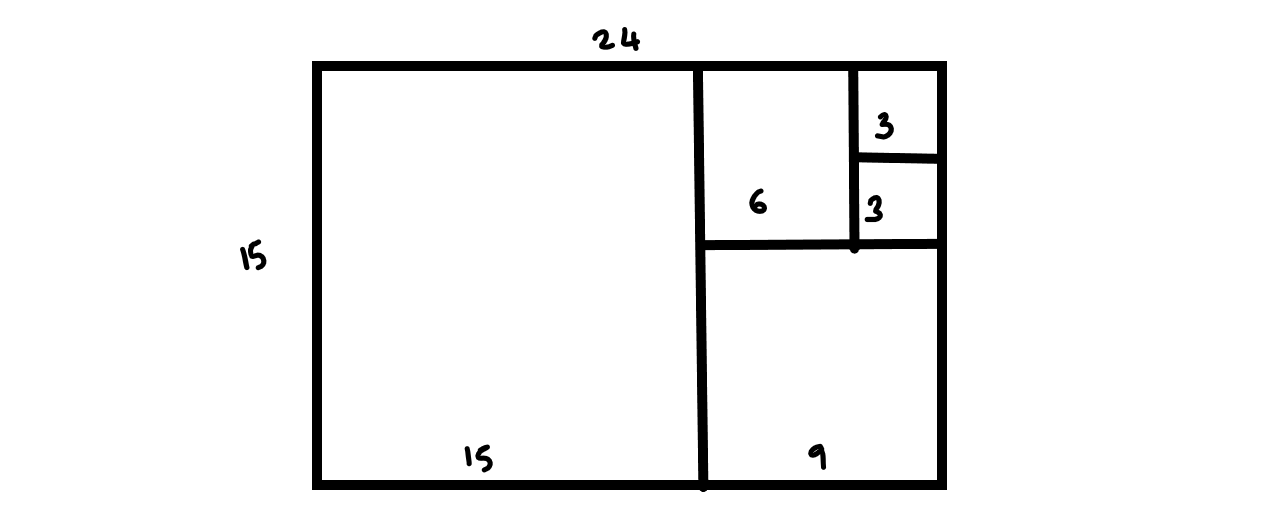

Here is a specific example with the numbers \(24\) and \(15\)

Figure 7.2: Picture showing Euclid’s algorithm pictorially for 24 and 15

7.2.2 Continued fractions

Another way of looking at Euclid’s algorithm is continued fractions. If \(a = qb+r\) then \[ \frac{a}{b} = q + \frac{r}{b}. \] If \(b = q_2 r + r_2\) then \[ \frac{b}{r} = q_2 + \frac{r_2}{r},\] so \[ \frac{a}{b} = q + \frac{1}{q_2 + \frac{r_2}{r}}. \] Continuing on like this we can express \[ \frac{a}{b} = q + \frac{1}{q_2 + \frac{1}{q_3 + \dots}}. \]

In a similar way if we take some real number \(x\) we can write it in continued fraction form by writing \(q_1 = [x]\) and \(q_2 = [1/(x-[x])]\) and so on. Unlike when expressing a rational number this process might not terminate.

In both situations we call this the continued fraction representation of a number.

7.2.3 Bezout’s lemma

The final statement in Euclid’s algorithm is called Bezout’s lemma

Lemma 7.2 (Bezout's Lemma) If \(a,b\) are two natural numbers then there exists \(x,y \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \[ gcd(a,b) = x a + b c. \]

As a result of this if \(a,b\) are coprime and \(n\) is any integer then there exists \(x, y \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \[ n = xa + yb.\]

Proof. We have already proved the first part in the discussion of Euclid’s algorithm.

For the second if \(a,b\) are coprime then \(gcd(a,b) =1\) (this is the definition of being coprime). Then by the first part of the theorem there exists \(\tilde{x}, \tilde{y} \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \[ 1= \tilde{x}a + \tilde{y}b, \] using this \[ n = (n\tilde{x})a + (n \tilde{y})b. \]

Using this we can show a powerful result which we have already seen

Theorem 7.3 Suppose that \(a,b \in \mathbb{N}\) and \(p\) is a prime number and \(p|ab\) then either \(p|a\) or \(p|b\).

If \(p|a\) then we are done so suppose that \(p\) does not divide \(a\). Then \(a,p\) are coprime so by Bezout’s lemma we can write \[1 = xa + yp\] and hence \[b = xab + ypb. \] As \(p|ab\) we know \(p|xab\) and from the expression we can see that \(p|ypb\) so \(p | (xab + ybp)\) so \(p|b\).

Lemma 7.3 If \(a|bc\) and \(gcd(a,b)=1\) then \(a|c\).

Proof. In a similar vein to above we can prove the fact we used when discussing least common multiples.

By Bezout’s lemma there exists \(x,y\) such that \(1=xa+yb\) then multplying through this gives \(c=xac +ybc\) then \(a|xac\) and \(a|ybc\) since \(a|bc\) so \(a|c\).

Now let us use this to prove the fundamental theorem of arithmetic again. Everything is a bit smoother now with more results.

Theorem 7.4 (Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic) Any natural number \(n\) has a unique factorisation into prime numbers.

Proof. First let us use strong induction to prove that there is a prime factorisation. The base case is \(n=2\) which is already in prime factorisation. Now suppose that every number less than \(n\) can be written as a product of prime factors. Then either \(n\) is prime, so it is in prime factorisation or \(n=ab\) then \(a,b < n\) so they have prime factorisations which allows us to write a prime factorisation for \(n\).

Second we want to prove this factorisation is unique. Suppose \(n = p_1 p_2 \dots p_k = q_1 q_2 \dots q_j\) where all the \(p_i, q_i\) are primes. Then \(p_1 | n\) so \(p_1|q_1\) or \(p_1 |q_2\dots q_j\). In the first case we must have \(p_1=q_1\) since \(q_1\) is prime. In the second case we have \(p_1|q_2\) or \(p_1 |q_3 \dots q_j\) and so on. We can keep itterating to show that \(p_1\) must appear in the list \(q_1, \dots q_j\). We can then repeat this with all the \(p_i\).

7.3 Chinese remainder theorem

Suppose we are interested in solving two or more linear congruences simultaneously.

Example 7.2 Suppose we would like to find \(x\) such that \(x \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, 3\) and \(x \equiv 3 \quad \mbox{mod} \, 4\). Then we can work modulo 12 since if we have a solution we can see we will get another solution by adding multiples of 12. If \(x \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, 3\) then modulo 12 \(x \equiv 1, 4, 7\) or \(10\). Similarly, if \(x \equiv 3 \quad \mbox{mod}\, 4\) then \(x \equiv 3, 7\) or \(11\) modulo 12. Therefore \(x \equiv 7\) modulo 12 is our unique solution up to adding multiples of 12.

Slightly differently suppose we would like to have \(x \equiv 2 \quad \mbox{mod} \, 6\) and \(x \equiv 3 \quad \mbox{mod} \, 4\) then again we want to work modulo 12. From the first constraint we have \(x \equiv 2\) or \(x \equiv 8\) and from the second we have \(x \equiv 3, 7\) or \(11\) as before. In this example we see there are no possible solutions.

Theorem 7.5 (Chinese Remainder Theorem) Suppose that \(n_1, \dots, n_k\) are pairwise coprime integers and \(a_1, \dots, a_k\) are integers with \(a_i \in [[n_i]]\) for every \(i\). Then there exists an integer \(x\) with \[ x \equiv a_i \quad \mbox{mod} n_i, \quad i = 1, \dots, k. \] Furthermore all the solutions are equivalent modulo \(N=n_1 \dots n_k\).

Proof. Let \(m_i = \Pi_{j \neq i} n_j\). Then \(n_i\) and \(m_i\) are coprime so by Euclid’s algorithm there exists \(x_i,y_i\) such that \(1 = x_i n_i + y_i m_i\) so \(e_i =y_i m_i = 1- x_i n_i\) so \(e_i \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n_i\) and \(e_i \equiv 0 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n_j\).

Then let \(x = \sum_{i=1}^k a_i e_i\) then this satisfies the conditions of the theorem.

Now suppose we have another \(y\) satisfying the congruences. Then \(x \equiv y \quad \mbox{mod} \, n_i\) for every \(i\). Therefore, \(n_i| |x-y|\) for every \(i\). Since all the \(n_i\) are coprime this means that \(N | |x-y|\).

Remark. The Chinese remainder theorem is very old. It dates back to Sunzi in the 3rd to 5th Century. It can be used to do apparently complicated computations very quickly and is used in important algorithms today such as RSA cryptography and Fast Fourier transform.

Lemma 7.4 If \(p\) is a prime and \(p \neq 2\) then the congruence \[ x^2 \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \,p \] has exactly two solutions.

Proof. Suppose \(x\) is a solution. Then \(x^2 \equiv 1\) modulo \(p\) then there is some \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\) such that \(x^2 = 1+kp\) so rearranging we have \((x-1)(x+1) = kp\). Using our result that \(p|ab\) implies \(p|a\) or \(p|b\) this tells us that \(p|(x+1)\) or \(p|(x-1)\). In which case \(x \equiv -1\) modulo \(p\) in the first case or \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(p\) in the second case.

N.b. in the case \(p=2\) this only gives one solution since \(1\equiv -1\) modulo 2.

Lemma 7.5 If \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) can be written as \(k\times j\) with \(k,j \neq 0,1,2, n\) and \(gcd(k,j)=1\) then the congruence \[ x^2 \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n \] has at least \(4\) solutions.

Proof. Arguing as in the previous proof there is some \(m\) such that \(x^2 = 1 + mkj\) so rearranging this gives \(mkj = (x+1)(x-1)\).

Now we can consider 4 possibilities.

Both \(k\) and \(j\) divide \(x+1\) in which case \(n|(x+1)\) since \(k\) and \(j\) are coprime. So \(x \equiv -1\) modulo \(n\).

Both \(k\) and \(j\) divide \(x-1\) in whcih case \(n|(x-1)\) since both \(k\) and \(j\) are coprime. So \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(n\).

\(k|(x+1)\) and \(j|(x-1)\) so \(x \equiv -1\) modulo \(k\) and \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(j\). In this case the chinese remainder theorem guarentees a solution to these two congruences simultaneously modulo \(nm\) and the solution cannot be equivalent to \(\pm 1\) modulo \(n\) since this would break one or other of the congruence modulo \(j\) or \(k\).

\(k|(x-1)\) and \(j|(x+1)\) so \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(k\) and \(x \equiv -1\) modulo \(j\). As with case \(3\) this gives another solution which must be different to the one in all previous cases.

Example 7.3 If \(n=77 = 7 \times 11\) then we can check all possible cases. We could have \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(77\) or \(x \equiv -1 \equiv 76\) modulo 77). These are case 1 and 2.

Or we could have \(x \equiv 1\) modulo \(7\) and \(x \equiv -1\) modulo \(11\) in which case we know by the chinese remainder theorem that there is a unique solution. To find it we need to follow the CRT proof strategy. \[11= 1\times 7 +4\] \[ 7 = 4 +3\] \[4 = 3+1\] So working backwards \[ 1=4-3\] \[ 1= 4 - (7-4) = 2 \times 4 -7\] \[ 1= 2\times(11-7) -7 = 2\times 11 -3\times 7\] So we have \(22\equiv 1 \, \mbox{mod} \,7\) and \(22 \equiv 0 \,\mbox{mod}\, 11\). We also have \(-21 \equiv 0 \, \mbox{mod} \,7\) and \(-21 \equiv 1 \, \mbox{mod} \,11\).

So If we take \[ x = 1 \times 22 + (-1)\times (-21) = 43 \] then we have another solution to our congruences which mimics case 3.

If we take \[ x=-1 \times 22 + 1 \times (-21) = -43\] and \(-43 \equiv 34\) modulo \(77\) so \(34\) gives us a fourth solution to the congruence.

Example 7.4 We can also see there are some case where \(n\) is not prime but we do have only two solutions to \[ x^2 \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod}\, n\]

For example if \(n=6\) we have \(1^2 \equiv 1, 2^2 \equiv 4, 3^2 \equiv 3, 4^2 \equiv 4, 5^2 \equiv 1\). This is because one of the factors of \(6\) is 2.

Similarly if \(n=9\) we cannot write it with factors which are coprime. In this case we have \(1^2 \equiv 1, 2^2 \equiv 4, 3^2 \equiv 0, 4^2 \equiv 7, 5^2 \equiv 7, 6^2 \equiv 0, 7^2 \equiv 4, 8^2 \equiv 1\).

7.4 Fermat’s Little Theorem and Euler’s Theorem

Definition 7.7 A number \(a\) is called a unit modulo \(n\) if there exists \(b\) such that \(ab = 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\). (We call \(b\) a multiplicative inverse modulo \(n\).)

Lemma 7.6 A number \(a\) is a unit modulo \(n\) if and only if \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime.

Proof. If \(a\) and \(n\) are coprime then \(1 = xa + yn\) in which case \(xa\equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\).

If there exists \(x\) such that \(xa \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\) then \(x a = 1 + y n\) and \(gcd(a,n) | (xa-yn)\) so \(gcd(a,n) = 1\).

Theorem 7.6 (Wilson's Theorem) Let \(p\) be a prime then \[ (p-1)! \equiv -1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p.\]

Proof. Given any \(a \in [[p]]\) we know that \(a\) is coprime to \(p\) so is a unit modulo \(p\) by the previous result.

Either we can pair up \(a\) with another number \(b \in [[p]]\) such that \(ab \equiv 1\) modulo \(p\) or \(a^2 \equiv 1\) modulo \(p\). There are only two solutions to the equation \(x^2 =1\) modulo \(p\) which are \(1\) and \(p-1 \equiv -1\). So each of \(2, \dots, p-2\) has a pair and this pair is unique since if \(ab \equiv 1\) and \(ac \equiv 1\) then we can multiply the first equation by \(c\) to get \(b \equiv 1\). Then the product \(2 \times 3 \times \dots \times (p-2)\) contains all the pairs so \[ 2 \times 3 \times \dots \times (p-2) \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p. \] Hence \[(p-1)! \equiv -1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p. \]

Remark. In fact we can go a bit further than Wilson’s theorem and say that \[ (n-1)! \equiv -1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\] if and only if \(n\) is prime.

If \(n\) is not prime and \(n \neq p^2\) for some prime then then there exists some \(k, j\) such that \(1< k,j < n\) and \(n=k\times j\). Then both \(k\) and \(j\) appear in the product \((n-1)!\) so \(n|(n-1)!\). Hence if \(n\) is not prime then \[ (n-1)! \equiv 0 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n \]

If \(n=p^2\) for a prime \(p \geq 3\) then both \(p\) and \(2p\) appear as factors in \((n-1)!\) so in this case \[ (n-1)! \equiv 0 \quad \mbox{mod}\, n. \]

Lastly if \(n=4\) then (uniquely) \[ (n-1)! \equiv 2 \mod n. \]

Definition 7.8 (Euler Totient Function) The Euler Totient function \(\phi(n)\) counts the number of natural numbers smaller than \(n\) that are coprime to \(n\). Alternatively the number of units modulo \(n\). Notice that \(\phi(1)=1\).

Lemma 7.7 If \(p\) is prime then \(\phi(p) = p-1\).

Example 7.5 Another example is \(n=12\) the numbers smaller than \(n\) which are coprime are \(1,5,7,11\) so \(\phi(12)=4\)

Lemma 7.8 If \(p\) is a prime then \[ \phi(p^k) = p^k - p^{k-1}. \]

Proof. The only way that \(gcd(m,p^k) \neq 1\) is if \(m\) is a multiple of \(p\). There are \(p^{k-1}\) multiples of \(p\) less than \(p^k\).

Lemma 7.9 If \(n\) and \(m\) are coprime integers then \[ \phi(nm) = \phi(n)\phi(m). \]

Proof. Recall that the units modulo \(n\) are exactly the numbers which are coprime to \(n\). Let us write the set of units modulo \(n\) as \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\).

Suppose that \(k\) is a unit modulo \(n\) and \(j\) is a unit modulo \(m\) then by the Chinese remainder theorem there exists a unique \(l\) such that \(l \equiv k \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\) and \(l \equiv j \quad \mbox{mod} \, m\). Equally if \(l\) is a unit modulo \(mn\) then there is some \(q\) such that \(lq \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod}\, mn\) so \(l\) is a unitt modulo \(n\) and a unit modulo \(m\). This shows we have a bijection between \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/n \mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times} \times \left(\mathbb{Z}/m \mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\) and \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/nm \mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\). Therefore the two sets have the same size. This gives our conclusion.

Proposition 7.1 We have a formula for Euler’s totient function given by \[ \phi(n) = n \Pi_{p \, prime, p|n} (1-1/p). \]

Proof. This follows from our previous results. By the fundamental theorem of arithmetic we can write \(n = p_1^{k_1} \dots p_j^{k_j}\) then \[\begin{align*} \phi(n) &= \phi(p_1^{k_1}) \dots \phi(p_j^{k_j}) \\ & = p_1^{k_1}(1-1/p_1) \dots p_j^{k_j}(1-1/p_j) \\ & = n (1-1/p_1) \dots (1-1/p_j). \end{align*}\]

Theorem 7.7 (Divisor sum) If \(n\) is an integer then \[ n = \sum_{d|n} \phi(d) \]

Proof. We prove this by strong induction. We can see that it is true when \(n=1\) then the only divisor of 1 is itself and \(\phi(1) =1\). This gives us the base case.

For the inductive step we assume that for all \(m < n\) we have \[ m = \sum_{d|m} \phi(d). \]

Then there are two cases. If \(n= p^k\) for some prime \(p\) and some positive integer \(k\) then the divisors of \(n\) are \(1,p, p^2, p^3, \dots, p^k\) so \[ \sum_{d|n} \phi(d) = 1 + (p-1) +(p^2-p) + \dots +(p^k - p^{k-1}) = p^k =n. \]

If \(n\) isn’t a prime power then \(n=kj\) for some \(k, j < n\) and \(gcd(k,j)=1\). \[\begin{align*} \sum_{d|n} \phi(d) &= \sum_{e|k} \sum_{f|j} \phi(ef) \\ & = \sum_{e|k} \sum_{f|j}\phi(e)\phi(f)\\ &= \left(\sum_{e|k} \phi(e)\right)\left(\sum_{f|j} \phi(f)\right)\\ & = kj = n. \end{align*}\]

Proposition 7.2 If \(p\) is prime and \(a\) is not a multiple of \(p\) then \[ a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p. \]

Proof. Let us consider \(a, 2a, 3a, \dots, (p-1)a\) as elements in \(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}\). We claim that they are all distinct. This is because since \(a,p\) are coprime, there exists \(x\) such that \(xa =1\) modulo \(p\). So if \(ka \equiv ja \quad, \mbox{mod} \,p\) then \(kab \equiv jab \quad \mbox{mod} \, p\) so \(k \equiv j \quad \mbox{mod}\, p\). So if \(k, j \in [[p]]\) this would imply \(k = j\).

So \(a, 2a, \dots, (p-1)a\) considered modulo \(p\) must be \(1, 2, \dots, (p-1)\) in some order. Hence \[ a \times 2a \times \dots \times (p-1)a \equiv (p-1)! \quad \mbox{mod}\, p. \] Which rewriting is \[ a^{p-1} (p-1)! \equiv (p-1)! \quad \mbox{mod} \, p. \] Now \((p-1)!\) is coprime to \(p\) since \(p\) is prime. So there exists \(c\) such that \(c(p-1)! \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod}\, p\) hence multiplying the equation above by \(c\) we get \[ a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p. \]

Theorem 7.8 (Fermat's Little Theorem) Suppose that \(gcd(a,n) =1\) then \(a^{\phi(n)} \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, n\).

Proof. The proof is very similar to above so I will leave the details to you!

Consider the set of integers {ka} where \(gcd(k,n) =1\) and \(k \in [[n]]\) and multiply them all together.

Definition 7.9 (primitive root) We say \(a\) is a primitive root modulo \(n\) if for every \(b \in \mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z}\) with \(gcd(b,n)=1\) there exists an \(x\) such that \(b \equiv a^x \quad \mbox{mod}\, n\).

You have hopefully seen in Algebra 1 that \((\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z})^{\times}\) is the set of elements in \(\mathbb{Z}/n\mathbb{Z}\) which have multiplicative inverses. This set forms a group under multiplication and the primitive roots are the generators of this group.

Example 7.6 Working modulo \(5\) the primitive roots are \(2,3\) we can see that \(4^2 = 1\) which means it cannot be a primitive root.

Lemma 7.10 Suppose that \(p\) is prime and \(r|p-1\) then there are exactly \(r\) elements, \(b\), of \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\) with \(b^r \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod}\, p\).

Proof (non-examinable). To prove this we have to consider polynomials equations modulo \(p\) (we can think of these like linear congruences). So for example the equation \[ a_0 + a_1 x + \dots + a_n x^n \equiv 0 \quad (mod \, p)\] There is a theorem called Lagrange’s theorem that says a polynomial of this form can have at most \(n\) solutions. (The proof is actually essentially the same as for a polynomial whose coefficients are real).

Now if \(x\) is an \(r^{th}\) root of unity then it is a solution to \[ x^r-1 \equiv 0 \quad (mod \, p).\] So we know by Lagranges theorem that there are at most \(r\) solutions to this polynomial.

We also know that if we write \(p-1=dk\) \[ x^{p-1} -1 \equiv (x^{d}-1)(x^{(k-1)d} + x^{(k-2)d} + \dots + 1) \quad (mod \, p).\] If we write \(P(x) = x^{(k-1)d} + x^{(k-2)d} + \dots + 1\) then we know \(P(x)\) has at most \((k-1)d\) solutions.

We also know that there are exactly \(p-1\) solutions to \(x^{p-1}-1 \equiv 0 \quad (mod\, p)\). This is because everything in \(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z}\) except 0 will be a solution.

So if \(x\) is a solution to \(x^{p-1} -1 \equiv 0 \quad (mod\, p)\) then we must have that either \(x^r-1 \equiv 0\) or \(P(x) \equiv 0\). This means that \(x^r -1\) must have at least \(r\) solutions. Therefore we have exactly \(r\).

Proposition 7.3 If \(p\) is prime and there exists an element \(a\) of order \(r\) then there are exactly \(\phi(r)\) elements of order \(r\).

Proof. Give an element \(a\) of order \(r\) then we have distinct elements \(a, a^2, \dots, a^{r-1}\). There are at most \(r\) elements \(b\) such that \(b^r \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod}\, p\) so these are all the possible elements of order less than or equal to \(r\). Now if \(gcd(k,r) = 1\) then for every \(m < r\) we have \(mk \not\equiv 0 \quad \mbox{mod} \, r\) so \(a^{mk} \not\equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p\). However \(a^{rk} \equiv 1 \quad \mbox{mod} \, p\). Therefore \(a^k\) is another element of order \(r\). Therefore we have at least \(\phi(r)\) elements of order \(r\).

Corollary 7.1 If \(p\) is prime then there are exactly \(\phi(p-1)\) primitive roots.

Proof. We know that the total number of elements in \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\) is \(\sum_{r} \mbox{number of elements of order}\, r\). We also know that the size of \(\left(\mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} \right)^{\times}\) is \(p-1\) and so there can only be elements of order \(r\) if \(r|p-1\).

We also know know that \(p-1 = \sum_{d|p-1} \phi(d)\). Putting all this together gives our result.