Chapter 6 Proof

Proof can be a difficult and subtle concept. During your first year you develop a good sense of proof by seeing lots of proofs. In this section we will work towards a rigorous notion of what a proof is and study some common proof techniques.

First, to show this is really necessary let us look at some false proofs.

Theorem 6.1 (untheorem) \[e^i =1\]

Proof (unproof). \[ e^i = (e^i)^{2\pi/2\pi} = (e^{2\pi i})^{1/2\pi} = 1^{1/2\pi} = 1.\]

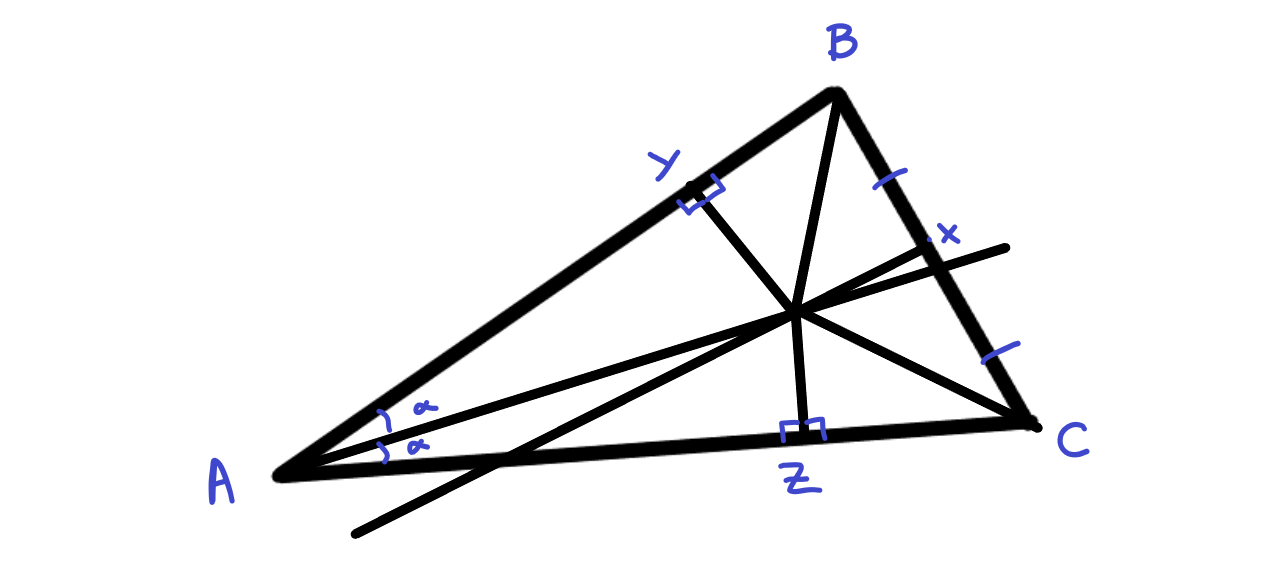

Theorem 6.2 (untheorem) All triangles are isoceles

Figure 6.1: A picture of a triangle

Consider the triangle \(ABC\). Draw the angle bisector at \(A\) and the perpendicular bisector of \(BC\). Call the point where these two intersect \(P\). Now draw a line from \(P\) to \(AB\) which is perpendicular to \(AB\) and call the intersection \(Y\) and draw a line from \(P\) to \(AC\) which is perpendicular to \(AC\) and call the intersection point \(Z\).

Now the triangles \(AYP\) and \(AZP\) are reflections of each other since they share two angles and a length. This means that the length \(AY\) is equal to the length \(AZ\) and the length \(YP\) is equal to \(ZP\).

Now the triangles \(BPX\) and \(APX\) are also reflections of each other since they both have right angles at \(X\) and share the two side lengths either side of the right angle. This implies that the lengths \(BP\) and \(CP\) are the same.

Then the triangles \(BPY\) and \(APZ\) are reflections of each other since they share two side lengths and a right angle. This means that the lengths \(BY\) and \(AZ\) are the same.

Now the length \(AB\) is equal to the lengths \(AY\) plus \(YB\) and the length \(AC\) is equal to the lengths \(AZ\) plus \(ZC\). Therefore \(AB = BC\).

Can you spot the problems in the proofs above? If they didn’t give obviously false results do you think you would notice that they were false.

6.1 Patterns of proof

In this section I am going to write proofs out using largely the language of logic. My hope is that it will make the different patterns of proof clear. In general it is neither necessary nor desirable to do this.

Definition 6.1 Proof by direct implication is the most straightforward kind of proof. Here we want to prove \(P \Rightarrow Q\).

Example 6.1 Suppose we want to prove that \(n\) being even implies that \(n^2\) is even. We can do this directly:

\[\begin{align*} & n \, \mbox{even} \, \Rightarrow \, \exists \, k \in \mathbb{N} \, s.t. n=2k, \\ & n = 2k \, \Rightarrow \, n^2 = (2k)^2 = 2 (2k^2), \\ & n^2 = 2(2k^2) \, \Rightarrow \, n^2 \, \mbox{even}. \end{align*}\]

So you see we just flow from one implication to the next.

Definition 6.2 (case-checking) Sometimes when proving something is always true we need to check it is true in several different cases. More interestingly sometimes to prove something is true in one instance we can check several cases.

Example 6.2 If we want to know whether or not it is possible for an irrational power of an irrational number to be rational we can consider a chain of cases.

\[ ((\sqrt{2})^{\sqrt{2}})^{\sqrt{2}} = (\sqrt{2})^2 = 2. \]

So either \(a=(\sqrt{2})^{\sqrt{2}}\) is rational (in which case it is an example of an irrational being taken to an irrational power and getting a rational) or it is irrational in which case \(a^{\sqrt{2}} =2\) is an example of an irrational number to an irrational number being rational.

Definition 6.3 Proof by contraposition is when we use the equivalence \((P\Rightarrow Q) \Leftrightarrow ((\neg Q) \Rightarrow (\neg P))\).

Example 6.3 Suppose we want to prove that if \(n\) is odd then \(n^2\) is odd by contraposition. We need to use the following facts:

(H1) If \(p\) is a prime and \(a,b \in \mathbb{N}\) then \(p|ab \, \Rightarrow (p|a)\vee(p|b)\).

(H2) 2 is a prime

We have:

\[\begin{align*} & \neg (n^2 \, \mbox{odd}) \, \Rightarrow \, (n^2 \, \mbox{even}), \\ & (n^2 \, \mbox{even}) \, \Rightarrow \, (\exists \, k \in \mathbb{N} \, s.t. \, n^2=2k) \\ & ((n^2=2k)\wedge(H1)\wedge(H2))\, \Rightarrow \,(2|n)\\ & (2|n)\, \Rightarrow \, \neg(n \, \mbox{odd})\\ & ((\neg(n^2 \, \mbox{odd})) \Rightarrow (\neg(n \, \mbox{odd})) \Rightarrow ((n \, \mbox{odd})\Rightarrow (n^2 \, \mbox{odd})) \end{align*}\]

Definition 6.4 (proof by contradiction) Proof by contradiction is when we use the fact that \((\neg P \Rightarrow F) \Rightarrow P\). So we assume the opposite of what we are trying to prove and get to a contradiction.

Example 6.4 Suppose we want to prove there does not exist any \(r \in \mathbb{Q}\) such that \(r^2=2\). Again first we need another results:

We say \(p,q \in \mathbb{Z}\) are coprime if there is no prime number \(k\) such that \(k|p\) and \(k|q\). Let us write the function \(coprime: \mathbb{Z}^2 \rightarrow \{T,F\}\) to tell us if two numbers are coprime.

If \(r \in \mathbb{Q}\) then there exists \(p,q \in \mathbb{Z}\) with \(coprime(p,q) =T\) such that \(r=p/q\)

\[\begin{align*} &\neg(\not\exists \, r \in \mathbb{Q} \, s.t. \, r^2 =2) \Rightarrow (\exists \, r \in \mathbb{Q} \, s.t. \, r^2 = 2)\\ &(\exists \, r \in \mathbb{Q} \, s.t. \, r^2 = 2) \Rightarrow (\exists \, p, q, \in \mathbb{Z} \, s.t. (p^2 = 2 q^2)\wedge((coprime(p,q)))) \\ &( p^2 = 2 q^2) \Rightarrow (2|p^2) \Rightarrow (2|p) \\ & (\exists \, p, q, \in \mathbb{Z} \, (p^2 = 2 q^2)\wedge(2|p)) \Rightarrow (\exists \, k \in \mathbb{Z} s.t.\, p=2k)\wedge(4k^2=2q^2) )\\ &(4k^2=2q^2) \Rightarrow (2k^2 = q^2) \Rightarrow (2|q)\\ &((2|p)\wedge(2|q)\wedge (coprime(p,q))) \Rightarrow F\\ &\neg(\not\exists \, r \in \mathbb{Q} \, s.t. \, r^2 =2) \Rightarrow F \end{align*}\]

Definition 6.5 Proof by construction. This method of proof is about showing that something exists.

Example 6.5 Suppose we want to prove that every quadratic equation with integer coefficients has at least one solution in \(\mathbb{C}\). i.e. we want to show if \(a,b,c \in \mathbb{Z}\) then the equation \[ ax^2+bx+c = 0 \] has at least one solution. We can check (and I’m sure you have before) that \[ x = \frac{-b\pm \sqrt{b^2-4ac}}{2a}, \] is a solution. So we have demonstrated the existence of at least one solution.

Another good example of proof by construction is the proof of Cantor-Schroeder-Bernstein.

6.2 Proof by induction

A particularly important pattern of proof is proof by induction. Induction is a key property of how the natural numbers work.

Definition 6.6 (proof by induction) Suppose that \(P\) is a property that could or could not hold for each natural number. We can think of \(P\) as a function \(\mathbb{N}\rightarrow \{T,F\}\). Suppose the following hold

\(P(0)=T\) (alternatively we say \(P(0)\) holds) - this is called the base case,

\(\forall \, n \in \mathbb{N} \, P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1)\) - this is called the inductive step,

then we can conclude that \(P(n)\) holds for every \(n\). We can write this as \(\forall n \in \mathbb{N} \, P(n)\).

Remark. Proof by induction works equivalently (by relabling things) if we start at \(n=1\) or in fact from any number \(k\) we just have to alter the conclusion to say \(\forall n \geq k \, P(n)\).

Example 6.6 Let \(P(n)\) be the statement that the sum of the first \(n\) odd numbers is \(n^2\).

Base case: For \(n=1\) the sum of the first odd number is \(1 = 1^2\).

Inductive step: Suppose that \[ \Sigma_{k=1}^n (2k-1) = n^2 \] then \[ \Sigma_{k=1}^{n+1} (2k-1) = n^2 + 2(n+1) -1 = n^2 +2n +1 = (n+1)^2. \] So we have shown \(P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1)\).

Therefore we have shown \(P(n)\) holds for all \(n \geq 1\).

Definition 6.7 (well ordering principle) Suppose that \(S \subset \mathbb{N}\) and \(S \neq \emptyset\) then \(S\) has a smallest element.

A classic example of using the well ordering principle is the prime factorisation theorem.

Theorem 6.3 (prime factorisation) Every \(n \in \mathbb{N}-\{0\}\) is the product of prime factors.

Proof. Let C be the set of all natural numbers that aren’t the product of prime factors. We want to show \(C\) is empty.

We assume for contradiction that \(C \neq \emptyset\) then by the well ordering principle \(C\) has a least element. Let us call this element \(m\).

If \(m\) only has divisors \(1\) and \(m\) then \(m\) is prime so is the product of prime factors which would be a contradiction.

If \(m\) has another divisor \(k \neq 1,m\) then we must have \(m=kj\) for some \(k, j \in \mathbb{N}-\{0\}\). This implies \(k, j < m\) so both \(k\) and \(j\) are the product of prime factors. This implies \(m\) is the product of prime factors which is a contradiction.

Therefore \(C\) must be empty.

Definition 6.8 (strong induction) Suppse \(P\) is a property that could or could not hold for each of the natural numbers. Suppose that the following are true.

\(P(0)\) holds,

If \(P(k)\) holds for all \(k<n\) then \(P(n)\) holds,

then we can conclude that \(P(n)\) holds for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\).

Theorem 6.4 (unique prime factorisation) Every natural number \(n \geq 2\) has a unique prime factorisation.

Proof. In this proof we are going to assume the fact that if \(p\) is a prime and \(p|ab\) then \(p|a\) or \(p|b\). If you are doing ma132 you will see this proved later.

For the base case \(2\) has a unique prime factorisation.

Suppose that for every \(k < n\) that \(k\) has a unique prime factorisation.

We already know that \(n\) has a prime factorisation from the prime factorisation theorem. It remains to show that it is unique.

Suppose that there are two prime factorisations

\[ n=p_1\dots p_k = q_1 \dots q_j. \]

By re-ordering we can assume that \(p_1 \leq p_2 \leq \dots\) and \(q_1 \leq q_2 \leq \dots\).

If \(p_1=q_1\) then \(n/p_1\) has a unique prime factorisation so we must have \(p_2=q_2\) etc.

If \(p_1 \neq q_1\) then without loss of generality \(p_1 < q_1\).

\[ p_1p_2 \dots p_k - p_1 q_2 q_3 \dots q_j = n (1-p_1/q_1) = (q_1-p_1)q_2\dots q_n.\]

If we call \(m = (q_1-p_1)q_2 \dots q_n\) then the expression on the left tells us that \(p_1|m\) and the expression on the right tells us that \(m < n\) since \(q_1-p_1 < q_1\). Therefore \(m\) has a unique prime factorisation and \(p_1|m\). We know that \(q_k > p_1\) for all \(k\) so we must have \(p_1|(q_1-p_1)\) but this would imply that \(p_1|q_1\) which is a contradiction to \(q_1\) being prime with \(p_1<q_1\). So we cannot have \(p_1 \neq q_1\).

Definition 6.9 (Recursion) Recursion is the name we give to constructing something inductively. A good example is the Fibonnacci numbers. Instead of having a rule for what the \(n^{th}\) Fibonnacci number is we say that \(F_{n+2} = F_{n+1} + F_{n}\) and \(F_0 = F_1 =1\).

Theorem 6.5 (Non-Examinable and not quite true) Induction, the well ordering principle and strong induction are all equivalent in the natural numbers.

Proof. As said in the name of the theorem this isn’t quite true for very subtle reasons. I think the result is still interesting.

(Induction \(\Rightarrow\) Well ordering principle): Given a set \(S \subset \mathbb{N}\) let us assume that \(S\) has no least element. Then let \(P(n)\) be the property than \(S \cap [[n]]= \emptyset\).

If \(0 \in S\) then \(0\) would be the least element of \(S\) so \(S \cap [[0]]= \emptyset\). This is the base case.

If \([[n]] \cap S = \emptyset\) then if \(n+1 \in S\) then \(n+1\) would be the least element of \(S\) so \([[n+1]] \cap S = \emptyset\).

Therefore induction implies that \(S = \bigcup_n (S \cap [[n]])\) is empty.

(Well ordering principle \(\Rightarrow\) strong induction):

Suppose that the well ordering principle holds and we have a property \(P\) such that \(P(0)\) holds and for every \(n\), \((P(k) \forall k<n) \Rightarrow P(n)\). Then set \(S\) be the set where \(P\) doesn’t hold. If \(S \neq \emptyset\) by well ordering it has a least element \(m\). By definition of \(S\) we must have \(P(k)\) holding for all \(k<m\) therefore we must have \(P(m)\) holds. This shows that \(S\) must be empty so \(P(n)\) holds for all \(n\).

(Strong induction \(\Rightarrow\) induction):

Suppose that strong induction holds and we have some property \(P\) such that \(P(0)\) holds and \(P(n) \Rightarrow P(n+1)\) for all \(n\). Then we also have \(P(k) \forall k< n \Rightarrow P(n)\) since \(P(k) \forall k < n \Rightarrow P(n-1) \Rightarrow P(n)\) so by strong induction \(P(n)\) holds for all \(n\).